The Project Gutenberg EBook of An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding,

Volume I., by John Locke

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding, Volume I.

MDCXC, Based on the 2nd Edition, Books I. and II. (of 4)

Author: John Locke

Release Date: January 6, 2004 [EBook #10615]

Last Updated: August 23, 2017

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HUMANE UNDERSTANDING, V1 ***

Produced by Steve Harris and David Widger

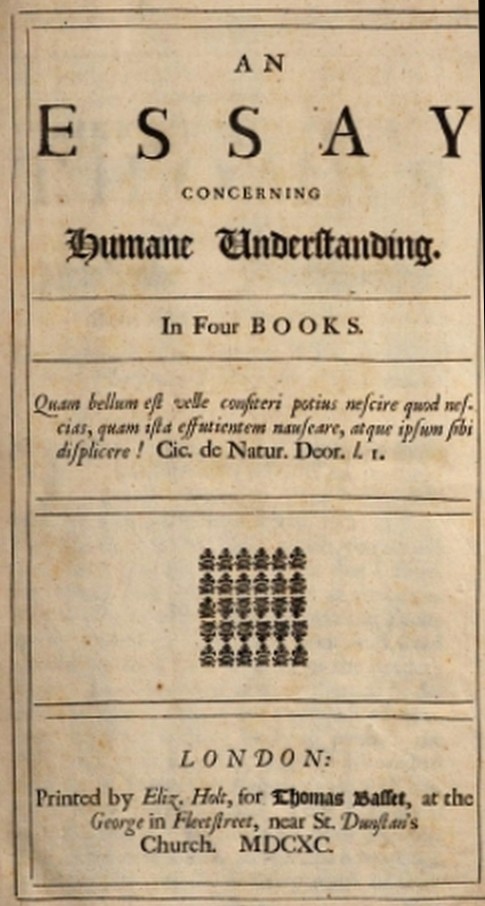

AN ESSAY CONCERNING HUMANE UNDERSTANDING

关于人道理解的文章

IN FOUR BOOKS

四本书中

By John Locke

作者:John Locke

Quam bellum est velle confiteri potius nescire quod nescias, quam ista effutientem nauseare, atque ipsum sibi displicere. —Cic. De Natur. Deor. 1. i.

Quam bellum est velle confiteri potius nescire quod nescias, quam ista effutientem nauseare, atque ipsum sibi displicere.-Cic.De Natur.迪尔。1. i.

LONDON: Printed by Eliz. Holt, for Thomas Basset, at the George in Fleet Street, near St. Dunstan’s Church.

伦敦:由Eliz.Holt, for Thomas Basset, at the George in Fleet Street, near St. Dunstan's Church.

MDCXC

MDCXC

CONTENTS

目 录

TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THOMAS, EARL OF PEMBROKE AND MONTGOMERY, BARON HERBERT OF CARDIFF LORD ROSS, OF KENDAL, PAR, FITZHUGH, MARMION, ST. QUINTIN, AND SHURLAND;

to the right honourable Thomas, earl of Pembroke and Montgomery, Baron Herbert of cardiff lord ross, of kendal, par, fitzhugh, marmion, st.Quintin, and Shurland;

LORD PRESIDENT OF HIS MAJESTY’S MOST HONOURABLE PRIVY COUNCIL; AND LORD LIEUTENANT OF THE COUNTY OF WILTS, AND OF SOUTH WALES.

英国国王最尊贵的枢密院主席;威尔斯郡和南威尔斯郡的中尉大人。

MY LORD,

我的主。

This Treatise, which is grown up under your lordship’s eye, and has ventured into the world by your order, does now, by a natural kind of right, come to your lordship for that protection which you several years since promised it. It is not that I think any name, how great soever, set at the beginning of a book, will be able to cover the faults that are to be found in it. Things in print must stand and fall by their own worth, or the reader’s fancy. But there being nothing more to be desired for truth than a fair unprejudiced hearing, nobody is more likely to procure me that than your lordship, who are allowed to have got so intimate an acquaintance with her, in her more retired recesses. Your lordship is known to have so far advanced your speculations in the most abstract and general knowledge of things, beyond the ordinary reach or common methods, that your allowance and approbation of the design of this Treatise will at least preserve it from being condemned without reading, and will prevail to have those parts a little weighed, which might otherwise perhaps be thought to deserve no consideration, for being somewhat out of the common road. The imputation of Novelty is a terrible charge amongst those who judge of men’s heads, as they do of their perukes, by the fashion, and can allow none to be right but the received doctrines. Truth scarce ever yet carried it by vote anywhere at its first appearance: new opinions are always suspected, and usually opposed, without any other reason but because they are not already common. But truth, like gold, is not the less so for being newly brought out of the mine. It is trial and examination must give it price, and not any antique fashion; and though it be not yet current by the public stamp, yet it may, for all that, be as old as nature, and is certainly not the less genuine. Your lordship can give great and convincing instances of this, whenever you please to oblige the public with some of those large and comprehensive discoveries you have made of truths hitherto unknown, unless to some few, from whom your lordship has been pleased not wholly to conceal them. This alone were a sufficient reason, were there no other, why I should dedicate this Essay to your lordship; and its having some little correspondence with some parts of that nobler and vast system of the sciences your lordship has made so new, exact, and instructive a draught of, I think it glory enough, if your lordship permit me to boast, that here and there I have fallen into some thoughts not wholly different from yours. If your lordship think fit that, by your encouragement, this should appear in the world, I hope it may be a reason, some time or other, to lead your lordship further; and you will allow me to say, that you here give the world an earnest of something that, if they can bear with this, will be truly worth their expectation. This, my lord, shows what a present I here make to your lordship; just such as the poor man does to his rich and great neighbour, by whom the basket of flowers or fruit is not ill taken, though he has more plenty of his own growth, and in much greater perfection. Worthless things receive a value when they are made the offerings of respect, esteem, and gratitude: these you have given me so mighty and peculiar reasons to have, in the highest degree, for your lordship, that if they can add a price to what they go along with, proportionable to their own greatness, I can with confidence brag, I here make your lordship the richest present you ever received. This I am sure, I am under the greatest obligations to seek all occasions to acknowledge a long train of favours I have received from your lordship; favours, though great and important in themselves, yet made much more so by the forwardness, concern, and kindness, and other obliging circumstances, that never failed to accompany them. To all this you are pleased to add that which gives yet more weight and relish to all the rest: you vouchsafe to continue me in some degrees of your esteem, and allow me a place in your good thoughts, I had almost said friendship. This, my lord, your words and actions so constantly show on all occasions, even to others when I am absent, that it is not vanity in me to mention what everybody knows: but it would be want of good manners not to acknowledge what so many are witnesses of, and every day tell me I am indebted to your lordship for. I wish they could as easily assist my gratitude, as they convince me of the great and growing engagements it has to your lordship. This I am sure, I should write of the UNDERSTANDING without having any, if I were not extremely sensible of them, and did not lay hold on this opportunity to testify to the world how much I am obliged to be, and how much I am,

这篇论文是在您的关注下成长起来的,并在您的命令下冒险进入了这个世界,现在,根据一种自然的权利,它来到您的身边,寻求您几年前承诺的保护。我不认为任何名字,无论多么伟大,放在一本书的开头,就能掩盖其中的缺点。印刷品必须以其自身的价值或读者的喜好来决定其成败。但是,对于真理来说,没有什么比一个公平的、没有偏见的听证会更值得期待的了,没有人比老爷更有可能为我争取到这一点,因为老爷被允许在她比较隐蔽的地方与她有过如此亲密的接触。众所周知,老爷对事物最抽象、最普遍的知识的推测已经有了很大的进展,超出了一般的范围或普通的方法,所以你对这篇论文的设计的允许和赞同,至少会使它不至于不经阅读就被谴责,而且会使那些可能被认为不值得考虑的部分稍加权衡,因为它们有些不符合常理。对新事物的指责在那些以时尚来判断人的头脑的人中是很可怕的,除了公认的教义,他们不允许有任何正确的东西。真理第一次出现时,几乎没有人通过投票把它带到任何地方:新的观点总是被怀疑,而且通常被反对,没有任何其他原因,只是因为它们还不普遍。但是,真理就像黄金一样,并不因为刚从矿井中出来而有所减少。它的价格是由试验和检验决定的,而不是由任何古老的时尚决定的;尽管它还没有被公众认可,但它可能和自然界一样古老,而且肯定不会更不真实。只要您愿意向公众介绍您对迄今为止不为人知的真理的一些重大而全面的发现,您就可以提供大量令人信服的例子,除非是对少数人,而您的主人并不愿意完全隐瞒它们。如果没有其他原因,仅此一点就足以让我把这篇论文献给老爷;它与老爷的那套更高尚、更庞大的科学体系中的某些部分有一些对应关系,老爷对其进行了如此新颖、准确和富有启发性的起草,如果老爷允许我夸口,我认为这已经很光荣了,我在这里和那里都陷入了一些与你不完全相同的想法。如果大人认为,在您的鼓励下,这应该出现在世界上,我希望这可以成为一个理由,在某个时候,引导大人进一步发展;您可以允许我说,您在这里给了世界一个预言,如果他们能忍受这个,将真正值得他们期待。大人,这说明我在这里给大人的礼物是什么;就像穷人给他的富人和大邻居的礼物一样,他的花篮或水果不会被人嫌弃,尽管他自己有更多的东西,而且更完美。不值钱的东西在被作为尊重、敬重和感激的祭品时就有了价值:你给了我如此强大和特殊的理由,让我在最高程度上为你的主人拥有这些东西,如果它们能给它们的东西增加一个价格,与它们本身的伟大相称,我可以自信地吹嘘,我在这里给你的主人带来了你所收到的最丰富的礼物。我确信,我有最大的义务寻求一切机会承认我从大人那里得到的一长串恩惠;这些恩惠虽然本身是巨大而重要的,但由于伴随着这些恩惠而来的远见卓识、关心和善意,以及其他令人感激的情况,使其更加重要。对于这一切,您还高兴地加上一句话,这句话给所有其他的事情带来了更大的分量和回味:您允许我继续受到您的某种程度的尊敬,并允许我在您的美好想法中占有一席之地,我几乎可以说是友谊。这一点,大人,您的言行在任何场合都不断地显示出来,甚至在我不在的时候也是如此,所以我提一下大家都知道的事情并不是虚荣心,但如果不承认这么多人见证的事情,并且每天都告诉我我对大人有恩,那就是没有礼貌了。我希望他们能帮助我表达感激之情,因为他们让我相信我对老爷的承诺是巨大的、不断增长的。我相信,如果我不是非常了解这些,我应该在没有任何了解的情况下写下UNDERSTANDING,而不是抓住这个机会向全世界证明我有多么的感激,以及我有多么的。

MY LORD,

我的主。

Your Lordship’s most humble and most obedient servant,

阁下最谦卑和最顺从的仆人。

JOHN LOCKE

约翰-罗克(JOHN LOCKE)

2 Dorset Court, 24th of May, 1689

多塞特法院2号,1689年5月24日

THE EPISTLE TO THE READER

给读者的书信

READER,

阅读者。

I have put into thy hands what has been the diversion of some of my idle and heavy hours. If it has the good luck to prove so of any of thine, and thou hast but half so much pleasure in reading as I had in writing it, thou wilt as little think thy money, as I do my pains, ill bestowed. Mistake not this for a commendation of my work; nor conclude, because I was pleased with the doing of it, that therefore I am fondly taken with it now it is done. He that hawks at larks and sparrows has no less sport, though a much less considerable quarry, than he that flies at nobler game: and he is little acquainted with the subject of this treatise—the UNDERSTANDING—who does not know that, as it is the most elevated faculty of the soul, so it is employed with a greater and more constant delight than any of the other. Its searches after truth are a sort of hawking and hunting, wherein the very pursuit makes a great part of the pleasure. Every step the mind takes in its progress towards Knowledge makes some discovery, which is not only new, but the best too, for the time at least.

我把我一些闲暇和繁重时间的消遣交给了你。如果这本书对你的任何一个人来说都是幸运的,而你在阅读时的乐趣只有我写这本书时的一半,你就会认为你的钱和我的努力一样,都是浪费的。不要误以为这是对我工作的赞扬;也不要因为我在做这件事时很高兴,就认为我现在对它很有好感。啄食云雀和麻雀的人,虽然猎物不多,但也不失为一种运动;而不知道这篇论文的主题--理解力--的人,就不会知道,由于它是灵魂中最崇高的能力,所以它比其他任何能力的运用都更大、更持久。它对真理的探索是一种捕猎和狩猎,其中的追求本身就是一种很大的乐趣。在追求知识的过程中,心灵的每一步都会有一些发现,这些发现不仅是新的,而且是最好的,至少在当时是这样。

For the understanding, like the eye, judging of objects only by its own sight, cannot but be pleased with what it discovers, having less regret for what has escaped it, because it is unknown. Thus he who has raised himself above the alms-basket, and, not content to live lazily on scraps of begged opinions, sets his own thoughts on work, to find and follow truth, will (whatever he lights on) not miss the hunter’s satisfaction; every moment of his pursuit will reward his pains with some delight; and he will have reason to think his time not ill spent, even when he cannot much boast of any great acquisition.

因为理解力,就像眼睛一样,只通过自己的视觉来判断对象,不能不对它所发现的东西感到高兴,对它所逃避的东西感到遗憾,因为它是未知的。因此,凡是把自己提高到救济篮之上,并且不满足于靠乞讨来的意见碎片懒散地生活,把自己的思想放在工作上,去寻找和追寻真理的人,(无论他照到什么)都不会错过猎人的满足感;他追求的每一刻都会以某种喜悦来回报他的痛苦;他有理由认为他的时间没有浪费,即使他不能夸耀有什么大收获。

This, Reader, is the entertainment of those who let loose their own thoughts, and follow them in writing; which thou oughtest not to envy them, since they afford thee an opportunity of the like diversion, if thou wilt make use of thy own thoughts in reading. It is to them, if they are thy own, that I refer myself: but if they are taken upon trust from others, it is no great matter what they are; they are not following truth, but some meaner consideration; and it is not worth while to be concerned what he says or thinks, who says or thinks only as he is directed by another. If thou judgest for thyself I know thou wilt judge candidly, and then I shall not be harmed or offended, whatever be thy censure. For though it be certain that there is nothing in this Treatise of the truth whereof I am not fully persuaded, yet I consider myself as liable to mistakes as I can think thee, and know that this book must stand or fall with thee, not by any opinion I have of it, but thy own. If thou findest little in it new or instructive to thee, thou art not to blame me for it. It was not meant for those that had already mastered this subject, and made a thorough acquaintance with their own understandings; but for my own information, and the satisfaction of a few friends, who acknowledged themselves not to have sufficiently considered it.

读者,这就是那些放任自己的思想并在写作中追随它们的人的娱乐;你不应该羡慕他们,因为如果你愿意在阅读中利用自己的思想,他们也会给你提供类似的消遣机会。如果它们是你自己的,我就是指它们:但如果它们是从别人那里得到的信任,它们是什么并不重要;它们不是在遵循真理,而是一些更卑鄙的考虑;如果他只是按照别人的指示说或想,那就不值得关心他说或想。如果你为自己判断,我知道你会坦率地判断,那么无论你怎么责备,我都不会受到伤害或冒犯。因为尽管可以肯定的是,这篇论文中没有任何我不完全相信的真理,但我认为自己和你一样容易犯错,并知道这本书必须在你那里站住脚,而不是根据我对它的任何看法,而是你自己的看法。如果你觉得书中没有什么新意或对你有启发,你也不能因此而责备我。这本书不是为那些已经掌握了这一主题,并对自己的理解有了全面了解的人准备的;而是为了让我自己了解,并让一些承认自己没有充分考虑的朋友满意。

Were it fit to trouble thee with the history of this Essay, I should tell thee, that five or six friends meeting at my chamber, and discoursing on a subject very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the difficulties that rose on every side. After we had awhile puzzled ourselves, without coming any nearer a resolution of those doubts which perplexed us, it came into my thoughts that we took a wrong course; and that before we set ourselves upon inquiries of that nature, it was necessary to examine our own abilities, and see what OBJECTS our understandings were, or were not, fitted to deal with. This I proposed to the company, who all readily assented; and thereupon it was agreed that this should be our first inquiry. Some hasty and undigested thoughts, on a subject I had never before considered, which I set down against our next meeting, gave the first entrance into this Discourse; which having been thus begun by chance, was continued by intreaty; written by incoherent parcels; and after long intervals of neglect, resumed again, as my humour or occasions permitted; and at last, in a retirement where an attendance on my health gave me leisure, it was brought into that order thou now seest it.

如果要让你知道这篇文章的来龙去脉,我应该告诉你,五六个朋友在我的房间里聚会,讨论一个非常遥远的话题,发现他们很快就陷入了困境,因为各方面都出现了困难。在我们困惑了一阵子之后,没有更接近解决那些令我们困惑的问题,我想到我们走错了路;在我们着手进行这种性质的调查之前,有必要检查我们自己的能力,看看我们的理解力是否适合处理什么问题。我向大家提出了这个建议,大家都欣然同意;于是,大家同意将此作为我们的第一次调查。一些匆忙而未消化的想法,关于我以前从未考虑过的问题,我把它们记下来,准备在下一次会议上讨论,这就是这篇论述的第一个入口;这篇论述在偶然的情况下开始,通过恳求而继续;通过不连贯的包裹而写;在长时间的忽视之后,在我的幽默感或场合允许的情况下,又重新开始;最后,在一个退休的地方,我的健康使我有时间,它被带到了你现在看到的这个顺序中。

This discontinued way of writing may have occasioned, besides others, two contrary faults, viz., that too little and too much may be said in it. If thou findest anything wanting, I shall be glad that what I have written gives thee any desire that I should have gone further. If it seems too much to thee, thou must blame the subject; for when I put pen to paper, I thought all I should have to say on this matter would have been contained in one sheet of paper; but the further I went the larger prospect I had; new discoveries led me still on, and so it grew insensibly to the bulk it now appears in. I will not deny, but possibly it might be reduced to a narrower compass than it is, and that some parts of it might be contracted, the way it has been writ in, by catches, and many long intervals of interruption, being apt to cause some repetitions. But to confess the truth, I am now too lazy, or too busy, to make it shorter. I am not ignorant how little I herein consult my own reputation, when I knowingly let it go with a fault, so apt to disgust the most judicious, who are always the nicest readers. But they who know sloth is apt to content itself with any excuse, will pardon me if mine has prevailed on me, where I think I have a very good one. I will not therefore allege in my defence, that the same notion, having different respects, may be convenient or necessary to prove or illustrate several parts of the same discourse, and that so it has happened in many parts of this: but waiving that, I shall frankly avow that I have sometimes dwelt long upon the same argument, and expressed it different ways, with a quite different design. I pretend not to publish this Essay for the information of men of large thoughts and quick apprehensions; to such masters of knowledge I profess myself a scholar, and therefore warn them beforehand not to expect anything here, but what, being spun out of my own coarse thoughts, is fitted to men of my own size, to whom, perhaps, it will not be unacceptable that I have taken some pains to make plain and familiar to their thoughts some truths which established prejudice, or the abstractedness of the ideas themselves, might render difficult. Some objects had need be turned on every side; and when the notion is new, as I confess some of these are to me; or out of the ordinary road, as I suspect they will appear to others, it is not one simple view of it that will gain it admittance into every understanding, or fix it there with a clear and lasting impression. There are few, I believe, who have not observed in themselves or others, that what in one way of proposing was very obscure, another way of expressing it has made very clear and intelligible; though afterwards the mind found little difference in the phrases, and wondered why one failed to be understood more than the other. But everything does not hit alike upon every man’s imagination. We have our understandings no less different than our palates; and he that thinks the same truth shall be equally relished by every one in the same dress, may as well hope to feast every one with the same sort of cookery: the meat may be the same, and the nourishment good, yet every one not be able to receive it with that seasoning; and it must be dressed another way, if you will have it go down with some, even of strong constitutions. The truth is, those who advised me to publish it, advised me, for this reason, to publish it as it is: and since I have been brought to let it go abroad, I desire it should be understood by whoever gives himself the pains to read it. I have so little affection to be in print, that if I were not flattered this Essay might be of some use to others, as I think it has been to me, I should have confined it to the view of some friends, who gave the first occasion to it. My appearing therefore in print being on purpose to be as useful as I may, I think it necessary to make what I have to say as easy and intelligible to all sorts of readers as I can. And I had much rather the speculative and quick-sighted should complain of my being in some parts tedious, than that any one, not accustomed to abstract speculations, or prepossessed with different notions, should mistake or not comprehend my meaning.

这种不连续的写作方式,除了其他原因外,可能还造成了两个相反的缺点,即:其中可能说得太少和太多。如果你发现有什么不足,我会很高兴我写的东西能让你希望我再进一步。如果你觉得太多,你必须责备这个问题;因为当我提笔写的时候,我认为我在这个问题上要讲的所有内容都会包含在一张纸上;但我越往前走,我的前景就越大;新的发现使我继续前进,所以它不由自主地发展到现在的规模。我不否认,它可能会被缩减到比现在更窄的范围内,它的某些部分可能会被收缩,它的写作方式,通过抓取,以及许多长时间的中断,很容易造成一些重复的内容。但要承认事实,我现在太懒了,或者说太忙了,无法使其缩短。我不是不知道,当我明知故犯地放任自己的错误时,我对自己的名声是多么的不屑一顾,因为这很容易让最有判断力的人感到厌恶,而他们总是最优秀的读者。但是,他们知道懒惰容易满足于任何借口,如果我的借口占了上风,请原谅我,我认为我有一个非常好的借口。因此,我不会在我的辩护中说,同一个概念,有不同的方面,可能方便或需要证明或说明同一论述的几个部分,而且这篇文章的许多部分都是如此:但放弃这一点,我将坦率地承认,我有时在同一个论点上花了很长时间,并以不同的方式表达它,但目的完全不同。我假装不是为了让那些思想深刻、理解力强的人了解这篇论文;对于这样的知识大师,我自称是个学者,因此事先警告他们,不要指望这里有什么东西,而是从我自己的粗浅思想中提炼出来的、适合我这样的人的东西,对他们来说,也许我花了一些功夫让他们的思想明白和熟悉一些真理,而这些真理的既定偏见或思想本身的抽象性可能会使他们难以接受。有些对象需要从每一个方面来考虑;当概念是新的,就像我承认其中一些概念对我来说是新的;或者是超出常规的,就像我怀疑它们在其他人看来是新的一样,不是一个简单的观点就能让它进入每个人的理解,或者以清晰而持久的印象将它固定在那里。我相信,很少有人没有在自己或他人身上看到,以一种方式提出的东西非常晦涩难懂,而以另一种方式表达的东西却非常清晰易懂;尽管事后人们发现这些短语没有什么不同,并想知道为什么一个人比另一个人更难理解。但是,每个人的想象力都不尽相同。我们的理解力不亚于我们的味觉;如果他认为每个人都能以同样的方式享受同样的真理,那么他就可能希望以同样的烹饪方式来款待每个人:肉可能是一样的,营养也很好,但不是每个人都能接受这种调料;如果你想让一些人,甚至是强壮的人接受它,就必须以另一种方式来打扮它。事实是,那些建议我出版这本书的人,因为这个原因,建议我按原样出版:既然我已经被带到国外,我希望不管是谁,只要花心思去读它,就应该理解它。我对印刷品没有什么好感,如果我不是因为这篇文章对别人有帮助而感到高兴,就像我认为它对我有帮助一样,我应该把它限制在一些朋友的视野中,是他们给了我这个机会。因此,我出现在印刷品中的目的是为了尽可能地发挥作用,我认为有必要使我要讲的东西对各种读者都尽可能地容易理解。我宁可让那些善于猜测、目光敏锐的人抱怨我在某些地方很乏味,也不愿让那些不习惯于抽象猜测、或对不同概念有偏好的人误解或不理解我的意思。

It will possibly be censured as a great piece of vanity or insolence in me, to pretend to instruct this our knowing age; it amounting to little less, when I own, that I publish this Essay with hopes it may be useful to others. But, if it may be permitted to speak freely of those who with a feigned modesty condemn as useless what they themselves write, methinks it savours much more of vanity or insolence to publish a book for any other end; and he fails very much of that respect he owes the public, who prints, and consequently expects men should read, that wherein he intends not they should meet with anything of use to themselves or others: and should nothing else be found allowable in this Treatise, yet my design will not cease to be so; and the goodness of my intention ought to be some excuse for the worthlessness of my present. It is that chiefly which secures me from the fear of censure, which I expect not to escape more than better writers. Men’s principles, notions, and relishes are so different, that it is hard to find a book which pleases or displeases all men. I acknowledge the age we live in is not the least knowing, and therefore not the most easy to be satisfied. If I have not the good luck to please, yet nobody ought to be offended with me. I plainly tell all my readers, except half a dozen, this Treatise was not at first intended for them; and therefore they need not be at the trouble to be of that number. But yet if any one thinks fit to be angry and rail at it, he may do it securely, for I shall find some better way of spending my time than in such kind of conversation. I shall always have the satisfaction to have aimed sincerely at truth and usefulness, though in one of the meanest ways. The commonwealth of learning is not at this time without master-builders, whose mighty designs, in advancing the sciences, will leave lasting monuments to the admiration of posterity: but every one must not hope to be a Boyle or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such masters as the great Huygenius and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some others of that strain, it is ambition enough to be employed as an under-labourer in clearing the ground a little, and removing some of the rubbish that lies in the way to knowledge;—which certainly had been very much more advanced in the world, if the endeavours of ingenious and industrious men had not been much cumbered with the learned but frivolous use of uncouth, affected, or unintelligible terms, introduced into the sciences, and there made an art of, to that degree that Philosophy, which is nothing but the true knowledge of things, was thought unfit or incapable to be brought into well-bred company and polite conversation. Vague and insignificant forms of speech, and abuse of language, have so long passed for mysteries of science; and hard and misapplied words, with little or no meaning, have, by prescription, such a right to be mistaken for deep learning and height of speculation, that it will not be easy to persuade either those who speak or those who hear them, that they are but the covers of ignorance, and hindrance of true knowledge. To break in upon the sanctuary of vanity and ignorance will be, I suppose, some service to human understanding; though so few are apt to think they deceive or are deceived in the use of words; or that the language of the sect they are of has any faults in it which ought to be examined or corrected, that I hope I shall be pardoned if I have in the Third Book dwelt long on this subject, and endeavoured to make it so plain, that neither the inveterateness of the mischief, nor the prevalency of the fashion, shall be any excuse for those who will not take care about the meaning of their own words, and will not suffer the significancy of their expressions to be inquired into.

我可能会被指责为一种巨大的虚荣心或无礼,假装要指导我们这个充满智慧的时代;当我承认我出版这篇论文是希望它对其他人有用时,这也算不上什么。但是,如果允许我们随意谈论那些假装谦虚地谴责他们自己写的东西毫无用处的人,我认为为任何其他目的出版一本书更有虚荣或无礼的味道;他非常不尊重他欠公众的那份尊重,因为他印刷并因此希望人们阅读,他不打算让他们遇到对自己或他人有用的东西。如果在这篇论述中没有发现其他可允许的东西,但我的设计不会停止;我的意图的良好性应该成为我目前的无价值的一些借口。主要是这一点使我免于受到指责的恐惧,我期望比更好的作家更能逃脱这种指责。人们的原则、观念和爱好是如此不同,以至于很难找到一本让所有的人都高兴或不高兴的书。我承认我们所处的时代不是最不了解的,因此也不是最容易满足的。如果我没有好运气去取悦别人,但也不应该得罪我。我明确地告诉我的所有读者,除了半打以外,这篇论文最初不是为他们准备的;因此,他们不需要费心去做这个数字。但是,如果有人认为适合对它进行愤怒和抨击,他可以放心地这样做,因为我将找到比这种谈话更好的方式来打发我的时间。我将永远感到满意,因为我真诚地追求真理和有用的东西,尽管是以一种最卑微的方式。在这个时代,学术界并非没有大师级的建设者,他们在推动科学发展方面的伟大设计将为后人留下永恒的纪念碑:但每个人都不能指望成为波义耳或西登纳姆;在这个时代,产生了像伟大的惠根尼斯和无可比拟的先生这样的大师。牛顿等大师的时代,能作为一个底层劳动者受雇于人,稍微清理一下地面,清除一些阻碍知识的垃圾,已经是很有志气了。如果聪明和勤劳的人的努力没有被学识渊博但轻率地使用不雅观、受影响或难以理解的术语所困扰,这些术语被引入科学,并在那里成为一种艺术,以至于哲学--除了对事物的真正了解--被认为不适合或不能够被带入有教养的公司和礼貌的谈话,那么世界上肯定会有更大的进步。模糊而无意义的言语形式,以及对语言的滥用,长期以来一直被当作科学的奥秘;而生硬而误用的词语,几乎没有任何意义,根据规定,有权利被误认为是深刻的学问和推测的高度,以至于不容易说服那些说话的人或听话的人,他们只是无知的幌子,阻碍真正的知识。闯入虚荣和无知的圣殿,我想对人类的理解会有一些帮助;尽管很少有人会认为他们在用词上会欺骗或被欺骗。我希望我在第三本书中对这一问题进行了长时间的讨论,并努力使它变得如此简单,以至于无论这种弊端的顽固性,还是这种时尚的盛行,都不能成为那些不注意自己话语的含义,不愿意让人探究其表达的意义的人的借口,我会得到原谅的。

I have been told that a short Epitome of this Treatise, which was printed in 1688, was by some condemned without reading, because INNATE IDEAS were denied in it; they too hastily concluding, that if innate ideas were not supposed, there would be little left either of the notion or proof of spirits. If any one take the like offence at the entrance of this Treatise, I shall desire him to read it through; and then I hope he will be convinced, that the taking away false foundations is not to the prejudice but advantage of truth, which is never injured or endangered so much as when mixed with, or built on, falsehood. In the Second Edition I added as followeth:—

有人告诉我,1688年印刷的这篇论文的简短摘要被一些人不加阅读地谴责,因为其中否认了先天观念;他们过于草率地得出结论,如果不假设先天观念,就不会有什么精神的概念或证明。如果有人对这篇论文的开头有同样的看法,我希望他能把它读完;然后我希望他能相信,消除错误的基础不是对真理的损害,而是对真理的好处,因为真理在与谬误混合或建立在谬误之上时,永远不会受到如此大的伤害或危害。在第二版中,我添加了以下内容:--

The bookseller will not forgive me if I say nothing of this New Edition, which he has promised, by the correctness of it, shall make amends for the many faults committed in the former. He desires too, that it should be known that it has one whole new chapter concerning Identity, and many additions and amendments in other places. These I must inform my reader are not all new matter, but most of them either further confirmation of what I had said, or explications, to prevent others being mistaken in the sense of what was formerly printed, and not any variation in me from it.

如果我对这个新版本只字不提,书商是不会原谅我的,他保证,这个新版本将通过其正确性来弥补前者的许多错误。他还希望人们知道,它有一个关于身份的全新章节,并在其他地方做了许多补充和修正。我必须告诉我的读者,这些并不都是新内容,而是大部分都是对我说过的话的进一步确认,或者是解释,以防止别人对以前印刷的内容产生误解,而不是我对它的任何改变。

I must only except the alterations I have made in Book II. chap. xxi.

我只必须排除我在第二册第二十一章中所作的改动。

What I had there written concerning Liberty and the Will, I thought deserved as accurate a view as I am capable of; those subjects having in all ages exercised the learned part of the world with questions and difficulties, that have not a little perplexed morality and divinity, those parts of knowledge that men are most concerned to be clear in. Upon a closer inspection into the working of men’s minds, and a stricter examination of those motives and views they are turned by, I have found reason somewhat to alter the thoughts I formerly had concerning that which gives the last determination to the Will in all voluntary actions. This I cannot forbear to acknowledge to the world with as much freedom and readiness; as I at first published what then seemed to me to be right; thinking myself more concerned to quit and renounce any opinion of my own, than oppose that of another, when truth appears against it. For it is truth alone I seek, and that will always be welcome to me, when or from whencesoever it comes. But what forwardness soever I have to resign any opinion I have, or to recede from anything I have writ, upon the first evidence of any error in it; yet this I must own, that I have not had the good luck to receive any light from those exceptions I have met with in print against any part of my book, nor have, from anything that has been urged against it, found reason to alter my sense in any of the points that have been questioned. Whether the subject I have in hand requires often more thought and attention than cursory readers, at least such as are prepossessed, are willing to allow; or whether any obscurity in my expressions casts a cloud over it, and these notions are made difficult to others’ apprehensions in my way of treating them; so it is, that my meaning, I find, is often mistaken, and I have not the good luck to be everywhere rightly understood.

我在那里写的关于自由和意志的内容,我认为应该得到我所能提供的最准确的看法;这些主题在各个时代都让世界上有学问的人遇到了问题和困难,这些问题和困难让道德和神学这些人们最关心的知识部分感到困惑。经过对人的思想工作的仔细检查,以及对他们的动机和观点的严格审查,我发现有理由改变我以前关于在所有自愿行动中给予意志最后决定的想法。我不能不以同样的自由和准备向世人承认这一点;就像我最初发表的在我看来是正确的东西一样;我认为自己更应该放弃和抛弃自己的任何观点,而不是反对别人的观点,当真理出现反对它时。因为我只追求真理,而且无论何时何地,我都欢迎真理的到来。但是,无论我有多大的勇气放弃我的任何观点,或者在我写的任何东西中出现任何错误的第一个证据时就退缩;但我必须承认,我还没有幸运地从那些针对我书中任何部分的印刷品的例外情况中得到任何启示,也没有从被敦促反对它的任何东西中找到理由来改变我在任何被质疑的地方的感觉。我手中的主题是否需要更多的思考和关注,而不是粗略的读者,至少是那些有倾向性的读者愿意允许的;或者我的表达方式中是否有任何晦涩难懂的地方给它蒙上了一层阴影,而这些概念在我处理它们的方式中变得难以理解;所以,我发现我的意思经常被误解,而我也没有好运地被到处正确地理解。

Of this the ingenious author of the Discourse Concerning the Nature of Man has given me a late instance, to mention no other. For the civility of his expressions, and the candour that belongs to his order, forbid me to think that he would have closed his Preface with an insinuation, as if in what I had said, Book II. ch. xxvii, concerning the third rule which men refer their actions to, I went about to make virtue vice and vice virtue, unless he had mistaken my meaning; which he could not have done if he had given himself the trouble to consider what the argument was I was then upon, and what was the chief design of that chapter, plainly enough set down in the fourth section and those following. For I was there not laying down moral rules, but showing the original and nature of moral ideas, and enumerating the rules men make use of in moral relations, whether these rules were true or false: and pursuant thereto I tell what is everywhere called virtue and vice; which “alters not the nature of things,” though men generally do judge of and denominate their actions according to the esteem and fashion of the place and sect they are of.

关于这一点,《关于人的本质的论述》的聪明作者给了我一个最新的例子,不提其他。因为他表达的礼貌和属于他的坦率,让我无法想象他在序言的结尾会有这样的暗示,好像我在第二册第二十七章中所说的,关于人的行为所依据的第三条规则,我打算把它说成是一种规则。除非他误解了我的意思;如果他认真考虑一下我当时的论点是什么,以及那一章的主要目的是什么,他就不会这样做了,这一点在第四节和后面的章节中已经说得很清楚。因为我在那里不是制定道德规则,而是说明道德观念的起源和性质,并列举了人们在道德关系中使用的规则,无论这些规则是真的还是假的:据此,我告诉了人们在各地被称为美德和恶习的东西;这 "没有改变事物的本质",尽管人们通常根据他们所在的地方和教派的尊敬和时尚来判断和命名他们的行为。

If he had been at the pains to reflect on what I had said, Bk. I. ch. ii. sect. 18, and Bk. II. ch. xxviii. sect. 13, 14, 15 and 20, he would have known what I think of the eternal and unalterable nature of right and wrong, and what I call virtue and vice. And if he had observed that in the place he quotes I only report as a matter of fact what OTHERS call virtue and vice, he would not have found it liable to any great exception. For I think I am not much out in saying that one of the rules made use of in the world for a ground or measure of a moral relation is—that esteem and reputation which several sorts of actions find variously in the several societies of men, according to which they are there called virtues or vices. And whatever authority the learned Mr. Lowde places in his Old English Dictionary, I daresay it nowhere tells him (if I should appeal to it) that the same action is not in credit, called and counted a virtue, in one place, which, being in disrepute, passes for and under the name of vice in another. The taking notice that men bestow the names of ‘virtue’ and ‘vice’ according to this rule of Reputation is all I have done, or can be laid to my charge to have done, towards the making vice virtue or virtue vice. But the good man does well, and as becomes his calling, to be watchful in such points, and to take the alarm even at expressions, which, standing alone by themselves, might sound ill and be suspected.

如果他不厌其烦地思考我所说的,Bk.I. ch. ii. sect.18, and Bk. II. ch. xxviii. sect.13、14、15和20节,他就会知道我对正确和错误的永恒和不可改变的性质,以及我所说的美德和恶习的看法。如果他注意到,在他引用的地方,我只是把别人所说的美德和恶习作为事实报告,他就不会发现有什么大的例外。因为我认为,我说世界上用来作为道德关系的基础或衡量标准的规则之一是,几种行为在人的几个社会中找到不同的尊重和声誉,根据这种尊重和声誉,它们被称为美德或恶习。无论博学的洛德先生在他的《古英语词典》中提到了什么权威,我敢说它没有任何地方告诉他(如果我呼吁它的话),同样的行为在一个地方没有信誉,被称为美德,而在另一个地方,由于不受欢迎,被称为恶习。注意到人们根据这一声誉规则赋予 "美德 "和 "恶习 "的名称,这就是我所做的,或者可以说是我所做的,使恶习成为美德或恶习。但是,好的人做得很好,就像他的工作一样,在这些方面保持警惕,甚至对那些单独的、可能听起来有问题并被怀疑的表达方式也保持警惕。

‘Tis to this zeal, allowable in his function, that I forgive his citing as he does these words of mine (ch. xxviii. sect. II): “Even the exhortations of inspired teachers have not feared to appeal to common repute, Philip, iv. 8;” without taking notice of those immediately preceding, which introduce them, and run thus: “Whereby even in the corruption of manners, the true boundaries of the law of nature, which ought to be the rule of virtue and vice, were pretty well preserved. So that even the exhortations of inspired teachers,” &c. By which words, and the rest of that section, it is plain that I brought that passage of St. Paul, not to prove that the general measure of what men called virtue and vice throughout the world was the reputation and fashion of each particular society within itself; but to show that, though it were so, yet, for reasons I there give, men, in that way of denominating their actions, did not for the most part much stray from the Law of Nature; which is that standing and unalterable rule by which they ought to judge of the moral rectitude and gravity of their actions, and accordingly denominate them virtues or vices. Had Mr. Lowde considered this, he would have found it little to his purpose to have quoted this passage in a sense I used it not; and would I imagine have spared the application he subjoins to it, as not very necessary. But I hope this Second Edition will give him satisfaction on the point, and that this matter is now so expressed as to show him there was no cause for scruple.

正是由于这种热心,在他的职能中是可以允许的,所以我原谅他引用了我的这些话(第二十八章,第二节)。"即使是受启发的教师的劝告也不怕诉诸于普通的声誉,菲利普,四,8;"而没有注意到紧接着的那些话,这些话介绍了它们,并这样说。"因此,即使在礼仪败坏的情况下,自然法则的真正界限,即应该成为美德和恶习的规则,也被很好地保留下来。因此,即使是受启发的教师的劝告,"等等。通过这句话和该节的其他部分,可以看出我把圣保罗的那段话拿来,并不是为了证明一般的人都是这样。保罗的这段话,并不是为了证明世界上人们所谓的美德和恶习的一般衡量标准是每个特定社会内部的声誉和时尚;而是为了表明,虽然是这样,但由于我在那里给出的理由,人们在这样称呼他们的行为时,大多数情况下并没有偏离自然法则;这是一个长期和不可改变的规则,他们应该据此判断其行为的道德正确性和严重性,并相应地将其称为美德或恶习。如果洛德先生考虑到这一点,他就会发现在我没有使用的意义上引用这段话对他的目的没有什么影响;而且我想他也会省去他对这段话的应用,因为这不是很有必要。但我希望第二版会让他在这一点上感到满意,而且这件事现在已经表达得很清楚了,让他知道没有理由再顾虑了。

Though I am forced to differ from him in these apprehensions he has expressed, in the latter end of his preface, concerning what I had said about virtue and vice, yet we are better agreed than he thinks in what he says in his third chapter (p. 78) concerning “natural inscription and innate notions.” I shall not deny him the privilege he claims (p. 52), to state the question as he pleases, especially when he states it so as to leave nothing in it contrary to what I have said. For, according to him, “innate notions, being conditional things, depending upon the concurrence of several other circumstances in order to the soul’s exerting them,” all that he says for “innate, imprinted, impressed notions” (for of innate IDEAS he says nothing at all), amounts at last only to this—that there are certain propositions which, though the soul from the beginning, or when a man is born, does not know, yet “by assistance from the outward senses, and the help of some previous cultivation,” it may AFTERWARDS come certainly to know the truth of; which is no more than what I have affirmed in my First Book. For I suppose by the “soul’s exerting them,” he means its beginning to know them; or else the soul’s ‘exerting of notions’ will be to me a very unintelligible expression; and I think at best is a very unfit one in this, it misleading men’s thoughts by an insinuation, as if these notions were in the mind before the ‘soul exerts them,’ i. e. before they are known;—whereas truly before they are known, there is nothing of them in the mind but a capacity to know them, when the ‘concurrence of those circumstances,’ which this ingenious author thinks necessary ‘in order to the soul’s exerting them,’ brings them into our knowledge.

虽然我不得不在他在序言的后半部分就我关于美德和恶习的说法所表达的这些忧虑中与他意见相左,但在他在第三章(第78页)关于 "自然的铭文和先天的观念 "的说法中,我们的意见比他认为的更一致。我不会拒绝他所要求的特权(第52页),即按他的意愿陈述问题,特别是当他陈述问题时,没有留下任何与我所说的相反的内容。因为,按照他的说法,"先天的观念是有条件的,取决于其他几种情况的同时发生,以便灵魂发挥它们",他为 "先天的、印记的、印象的观念 "所说的一切(因为对于先天的观念,他根本没有说)。最后,他只说了这样一句话:有些命题,虽然灵魂从一开始,或者当一个人出生时,并不知道,但 "通过外在感官的帮助,以及以前一些培养的帮助,"它可能在以后肯定会知道其真相。这不外乎是我在第一本书中所申明的。因为我想,他所说的 "灵魂发挥它们的作用 "是指它开始认识它们;否则,灵魂 "发挥概念 "对我来说是一个非常难以理解的表达方式;我认为在这一点上最多是一个非常不合适的表达方式,它通过暗示来误导人们的思想,好像这些概念在 "灵魂发挥它们的作用",即在认识它们之前就已经在头脑中了。而实际上在它们被认识之前,它们在头脑中没有任何东西,只有认识它们的能力,当 "那些情况的同时发生 "时,这位聪明的作者认为 "为了让灵魂发挥它们",必须把它们带入我们的知识。

P. 52 I find him express it thus: ‘These natural notions are not so imprinted upon the soul as that they naturally and necessarily exert themselves (even in children and idiots) without any assistance from the outward senses, or without the help of some previous cultivation.’ Here, he says, they ‘exert themselves,’ as p. 78, that the ‘soul exerts them.’ When he has explained to himself or others what he means by ‘the soul’s exerting innate notions,’ or their ‘exerting themselves;’ and what that ‘previous cultivation and circumstances’ in order to their being exerted are—he will I suppose find there is so little of controversy between him and me on the point, bating that he calls that ‘exerting of notions’ which I in a more vulgar style call ‘knowing,’ that I have reason to think he brought in my name on this occasion only out of the pleasure he has to speak civilly of me; which I must gratefully acknowledge he has done everywhere he mentions me, not without conferring on me, as some others have done, a title I have no right to.

P.52 我发现他是这样表达的。'这些自然的观念并没有在灵魂上打下烙印,以至于它们自然而然地、必然地发挥自己的作用(甚至在儿童和白痴身上),而不需要外在感官的任何帮助,也不需要先前的某种培养。在这里,他说,它们'发挥自己',正如第78页所说的'灵魂发挥它们'。当他向自己或别人解释了他所说的'灵魂发挥先天的概念'或它们'发挥自己'的意思;以及为了发挥它们的'先前的培养和环境'是什么时,我想他会发现在这一点上我和他之间的争议很小,只是他称'发挥概念',而我以更粗俗的方式称之为'认识',所以我有理由认为他在这个场合提起我的名字只是出于他对我说文明的乐趣。我必须感激地承认,他在提到我的任何地方都做到了这一点,而不是像其他一些人那样,把一个我无权使用的头衔赋予我。

There are so many instances of this, that I think it justice to my reader and myself to conclude, that either my book is plainly enough written to be rightly understood by those who peruse it with that attention and indifferency, which every one who will give himself the pains to read ought to employ in reading; or else that I have written mine so obscurely that it is in vain to go about to mend it. Whichever of these be the truth, it is myself only am affected thereby; and therefore I shall be far from troubling my reader with what I think might be said in answer to those several objections I have met with, to passages here and there of my book; since I persuade myself that he who thinks them of moment enough to be concerned whether they are true or false, will be able to see that what is said is either not well founded, or else not contrary to my doctrine, when I and my opposer come both to be well understood.

这样的例子太多了,所以我认为对我的读者和我自己来说,可以得出这样的结论:要么我的书写得很清楚,足以让那些以关注和漠不关心的态度来阅读的人正确地理解,而这是每个愿意花心思阅读的人在阅读时应该采用的方式;要么我的书写得很模糊,去修补它是徒劳的。无论哪种说法是真的,受影响的只是我自己;因此,我将不再麻烦我的读者,对我遇到的那些反对意见,对我书中的一些段落,我认为可以说些什么;因为我相信,只要他认为这些反对意见足够重要,足以关心它们是真的还是假的,就能看到所说的不是没有根据,就是没有违背我的教义,当我和我的反对者都被充分理解时。

If any other authors, careful that none of their good thoughts should be lost, have published their censures of my Essay, with this honour done to it, that they will not suffer it to be an essay, I leave it to the public to value the obligation they have to their critical pens, and shall not waste my reader’s time in so idle or ill-natured an employment of mine, as to lessen the satisfaction any one has in himself, or gives to others, in so hasty a confutation of what I have written.

如果有其他作者,小心翼翼地防止他们的好想法被遗失,发表了他们对我的文章的指责,并对它给予了这样的荣誉,即他们不会让它成为一篇文章,我让公众去重视他们对批评之笔的义务,并且不会在我的这种闲置或不成熟的工作中浪费读者的时间,以减少任何人对自己的满意,或给其他人,对我所写的东西进行如此草率的驳斥。

The booksellers preparing for the Fourth Edition of my Essay, gave me notice of it, that I might, if I had leisure, make any additions or alterations I should think fit. Whereupon I thought it convenient to advertise the reader, that besides several corrections I had made here and there, there was one alteration which it was necessary to mention, because it ran through the whole book, and is of consequence to be rightly understood. What I thereupon said was this:—

准备出版我的《论语》第四版的书商给了我通知,如果我有时间,我可以做任何我认为合适的补充或修改。于是我认为有必要通知读者,除了我在这里和那里做的几处更正外,还有一处改动是必须提及的,因为它贯穿全书,对正确理解有重要影响。我当时是这样说的:----。

CLEAR and DISTINCT ideas are terms which, though familiar and frequent in men’s mouths, I have reason to think every one who uses does not perfectly understand. And possibly ‘tis but here and there one who gives himself the trouble to consider them so far as to know what he himself or others precisely mean by them. I have therefore in most places chose to put DETERMINATE or DETERMINED, instead of CLEAR and DISTINCT, as more likely to direct men’s thoughts to my meaning in this matter. By those denominations, I mean some object in the mind, and consequently determined, i. e. such as it is there seen and perceived to be. This, I think, may fitly be called a determinate or determined idea, when such as it is at any time objectively in the mind, and so determined there, it is annexed, and without variation determined, to a name or articulate sound, which is to be steadily the sign of that very same object of the mind, or determinate idea.

清晰和明确的概念是一些术语,虽然在人们口中很熟悉,也很常见,但我有理由认为每一个使用的人都不完全理解。可能只有在这里和那里,才会有一个人不厌其烦地考虑它们,以至于知道他自己或其他人对它们的确切含义。因此,我在大多数地方选择用DETERMINATE或DETERMINED,而不是CLEAR和DISTINCT,因为这样更有可能引导人们的思维,使他们理解我在这个问题上的意思。通过这些名称,我指的是头脑中的一些对象,并因此而确定,也就是说,它是在那里看到和感知到的。我认为,当它在任何时候客观地存在于心灵中,并在那里被确定下来时,它被附在一个名称或发音上,并且没有变化地被确定下来,而这个名称或发音将稳定地成为心灵中的那个对象或确定的概念的标志,这就可以适当地被称为确定的或确定的概念。

To explain this a little more particularly. By DETERMINATE, when applied to a simple idea, I mean that simple appearance which the mind has in its view, or perceives in itself, when that idea is said to be in it: by DETERMINED, when applied to a complex idea, I mean such an one as consists of a determinate number of certain simple or less complex ideas, joined in such a proportion and situation as the mind has before its view, and sees in itself, when that idea is present in it, or should be present in it, when a man gives a name to it. I say SHOULD be, because it is not every one, nor perhaps any one, who is so careful of his language as to use no word till he views in his mind the precise determined idea which he resolves to make it the sign of. The want of this is the cause of no small obscurity and confusion in men’s thoughts and discourses.

请更具体地解释一下这一点。DETERMINATE,当应用于一个简单的概念时,我的意思是,当这个概念被说成是在它里面时,它的头脑在它的视野中,或者在它本身中感知到的那个简单的外观:DETERMINED,当应用于一个复杂的概念时,我的意思是,当这个概念存在于它里面,或者应该存在于它里面,当一个人给它命名时,它是由确定数量的某些简单或不太复杂的概念组成的,以它的视野中的比例和情况结合起来,并且在它本身看到。我说应该是,因为不是每一个人,也许也不是任何一个人,对自己的语言如此谨慎,直到他在头脑中看到他决心使之成为标志的确切的确定的想法时才使用任何一个词。这一点的缺失是导致人们的思想和讨论中出现不小的模糊和混乱的原因。

I know there are not words enough in any language to answer all the variety of ideas that enter into men’s discourses and reasonings. But this hinders not but that when any one uses any term, he may have in his mind a determined idea, which he makes it the sign of, and to which he should keep it steadily annexed during that present discourse. Where he does not, or cannot do this, he in vain pretends to clear or distinct ideas: it is plain his are not so; and therefore there can be expected nothing but obscurity and confusion, where such terms are made use of which have not such a precise determination.

我知道在任何语言中都没有足够的词汇来回答进入人们讨论和推理中的所有各种想法。但这并不妨碍任何人在使用任何术语时,在他的脑海里有一个确定的想法,他把这个想法作为标志,并在当前的讨论中稳定地把它附在上面。如果他不这样做,或者不能这样做,他就会徒劳地假装有清晰或明确的想法:很明显,他的想法不是这样的;因此,在使用这种没有精确确定的术语的地方,除了模糊和混乱之外,不可能有什么期待。

Upon this ground I have thought determined ideas a way of speaking less liable to mistakes, than clear and distinct: and where men have got such determined ideas of all that they reason, inquire, or argue about, they will find a great part of their doubts and disputes at an end; the greatest part of the questions and controversies that perplex mankind depending on the doubtful and uncertain use of words, or (which is the same) indetermined ideas, which they are made to stand for. I have made choice of these terms to signify, (1) Some immediate object of the mind, which it perceives and has before it, distinct from the sound it uses as a sign of it. (2) That this idea, thus determined, i.e. which the mind has in itself, and knows, and sees there, be determined without any change to that name, and that name determined to that precise idea. If men had such determined ideas in their inquiries and discourses, they would both discern how far their own inquiries and discourses went, and avoid the greatest part of the disputes and wranglings they have with others.

基于这一点,我认为确定的概念是一种不容易出错的说话方式,而不是清晰明确的:如果人们对他们推理、询问或争论的一切都有这种确定的概念,他们就会发现他们的大部分疑问和争论都结束了;使人类困惑的问题和争论的最大部分取决于对词语的可疑和不确定的使用,或(这是同)不确定的概念,它们被用来代表。我选择这些术语是为了表示:(1)心灵的某些直接对象,它感知到并在它面前,与它用作标志的声音不同。(2) 这样确定的理念,即心灵本身所拥有的,知道的,在那里看到的,被确定为没有任何变化的名称,而该名称被确定为该精确的理念。如果人们在他们的调查和讨论中有这种确定的想法,他们就会发现他们自己的调查和讨论有多远,并避免他们与他人的最大部分争议和争吵。

Besides this, the bookseller will think it necessary I should advertise the reader that there is an addition of two chapters wholly new; the one of the Association of Ideas, the other of Enthusiasm. These, with some other larger additions never before printed, he has engaged to print by themselves, after the same manner, and for the same purpose, as was done when this Essay had the second impression.

除此以外,书商会认为我有必要告诉读者,这里增加了两章全新的内容;一章是思想的联系,另一章是热情。这两章以及其他一些以前从未印刷过的较大的补充内容,他已承诺按照同样的方式和目的自行印刷,就像这篇论文第二版时那样。

In the Sixth Edition there is very little added or altered. The greatest part of what is new is contained in the twenty-first chapter of the second book, which any one, if he thinks it worth while, may, with a very little labour, transcribe into the margin of the former edition.

在第六版中,增加或改变的内容很少。大部分新内容都包含在第二本书的第21章中,任何人如果认为值得,都可以用很少的精力将其抄写在前一版本的空白处。

ESSAY CONCERNING HUMAN UNDERSTANDING.

关于人类理解的文章。

INTRODUCTION.

引言。

1. An Inquiry into the Understanding pleasant and useful.

1.对理解愉快和有用的探索。

Since it is the UNDERSTANDING that sets man above the rest of sensible beings, and gives him all the advantage and dominion which he has over them; it is certainly a subject, even for its nobleness, worth our labour to inquire into. The understanding, like the eye, whilst it makes us see and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself; and it requires and art and pains to set it at a distance and make it its own object. But whatever be the difficulties that lie in the way of this inquiry; whatever it be that keeps us so much in the dark to ourselves; sure I am that all the light we can let in upon our minds, all the acquaintance we can make with our own understandings, will not only be very pleasant, but bring us great advantage, in directing our thoughts in the search of other things.

既然是理解力使人凌驾于其他可感知的生命之上,并使他拥有对他们的所有优势和支配权;那么,即使是为了它的高尚,它也肯定是一个值得我们努力探究的主题。理解力,就像眼睛一样,虽然它使我们看到和感知所有其他事物,但却没有注意到它自己;它需要艺术和努力,把它放在远处,使它成为自己的目标。但是,不管在这种探究的道路上有什么困难;不管是什么让我们对自己如此蒙在鼓里;我确信,我们能让我们的思想得到的所有光亮,我们能与我们自己的理解相识,不仅会非常愉快,而且会给我们带来巨大的好处,引导我们的思想去寻找其他事物。

2. Design.

2.设计。

This, therefore, being my purpose—to inquire into the original, certainty, and extent of HUMAN KNOWLEDGE, together with the grounds and degrees of BELIEF, OPINION, and ASSENT;—I shall not at present meddle with the physical consideration of the mind; or trouble myself to examine wherein its essence consists; or by what motions of our spirits or alterations of our bodies we come to have any SENSATION by our organs, or any IDEAS in our understandings; and whether those ideas do in their formation, any or all of them, depend on matter or not. These are speculations which, however curious and entertaining, I shall decline, as lying out of my way in the design I am now upon. It shall suffice to my present purpose, to consider the discerning faculties of a man, as they are employed about the objects which they have to do with. And I shall imagine I have not wholly misemployed myself in the thoughts I shall have on this occasion, if, in this historical, plain method, I can give any account of the ways whereby our understandings come to attain those notions of things we have; and can set down any measures of the certainty of our knowledge; or the grounds of those persuasions which are to be found amongst men, so various, different, and wholly contradictory; and yet asserted somewhere or other with such assurance and confidence, that he that shall take a view of the opinions of mankind, observe their opposition, and at the same time consider the fondness and devotion wherewith they are embraced, the resolution and eagerness wherewith they are maintained, may perhaps have reason to suspect, that either there is no such thing as truth at all, or that mankind hath no sufficient means to attain a certain knowledge of it.

因此,这就是我的目的--探究人类知识的原始性、确定性和范围,以及信仰、观点和认同的理由和程度;我目前不会去管心灵的物理考虑。我现在不会去管心灵的物理问题,也不会去研究它的本质是什么;或者通过我们的精神的运动或我们身体的改变,我们的器官会产生任何感觉,或者我们的理解会产生任何想法;以及这些想法的形成,任何或所有的想法,是否取决于物质。这些猜测,无论多么好奇和有趣,我都会拒绝,因为在我现在的设计中,这些猜测已经超出了我的范围。就我目前的目的而言,考虑一下人的辨别能力就足够了,因为它们被用于与之相关的对象。如果我能够用这种历史性的、朴素的方法,说明我们的理解力是如何达到我们对事物的那些概念的;能够对我们知识的确定性提出任何措施;或者对那些在人与人之间发现的、如此不同的、完全矛盾的信念的理由,我想我在这个场合并没有完全误用自己的想法。然而,在某处以如此肯定和自信的方式断言,如果他看到人类的观点,观察他们的反对意见,同时考虑到他们所接受的喜爱和奉献,以及他们所坚持的决心和热切,也许有理由怀疑,要么根本就没有所谓的真理,要么人类没有足够的手段来达到对真理的确定认识。

3. Method.

3.方法。

It is therefore worth while to search out the bounds between opinion and knowledge; and examine by what measures, in things whereof we have no certain knowledge, we ought to regulate our assent and moderate our persuasion. In order whereunto I shall pursue this following method:— First, I shall inquire into the original of those ideas, notions, or whatever else you please to call them, which a man observes, and is conscious to himself he has in his mind; and the ways whereby the understanding comes to be furnished with them.

因此,我们有必要找出意见和知识之间的界限;并研究在我们没有确切知识的情况下,我们应该通过什么措施来调节我们的同意和缓和我们的说服力。为此,我将采取以下方法:--首先,我将探究人所观察到的、自己意识到的、在其头脑中拥有的那些观念、概念或其他任何你想称之为的东西的起源;以及理解力获得它们的方式。

Secondly, I shall endeavour to show what knowledge the understanding hath by those ideas; and the certainty, evidence, and extent of it.

其次,我将努力说明理解力通过这些观念所拥有的知识;以及它的确定性、证据和范围。

Thirdly, I shall make some inquiry into the nature and grounds of FAITH or OPINION: whereby I mean that assent which we give to any proposition as true, of whose truth yet we have no certain knowledge. And here we shall have occasion to examine the reasons and degrees of ASSENT.

第三,我将对 "信仰 "或 "观点 "的性质和理由进行一些调查:我指的是我们对任何命题的真实性给予的同意,但我们对其真实性并没有确定的认识。在这里,我们将有机会研究 "同意 "的原因和程度。

4. Useful to know the Extent of our Comprehension.

4.有助于了解我们的理解力的程度。

If by this inquiry into the nature of the understanding, I can discover the powers thereof; how far they reach; to what things they are in any degree proportionate; and where they fail us, I suppose it may be of use to prevail with the busy mind of man to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its comprehension; to stop when it is at the utmost extent of its tether; and to sit down in a quiet ignorance of those things which, upon examination, are found to be beyond the reach of our capacities. We should not then perhaps be so forward, out of an affectation of an universal knowledge, to raise questions, and perplex ourselves and others with disputes about things to which our understandings are not suited; and of which we cannot frame in our minds any clear or distinct perceptions, or whereof (as it has perhaps too often happened) we have not any notions at all. If we can find out how far the understanding can extend its view; how far it has faculties to attain certainty; and in what cases it can only judge and guess, we may learn to content ourselves with what is attainable by us in this state.

如果通过对理解力的性质的调查,我可以发现它的能力;它们能达到多远;它们与哪些事物在任何程度上是相称的;以及它们在哪些方面让我们失望,我想这可能有助于说服人的忙碌的头脑,使其在处理超出其理解力的事物时更加谨慎;在它达到其最大限度时停止;并在安静地无视那些经检查发现超出我们能力范围的事物中坐下来。这样,我们也许就不应该出于一种普遍知识的影响,提出问题,使自己和他人对我们的理解不适合的事物产生争论;对我们无法在头脑中形成任何清晰或明确的认识,或者(也许经常发生)我们根本没有任何概念的事物感到困惑。如果我们能找出理解力能在多大程度上扩展它的视野;它在多大程度上有能力达到确定性;以及在哪些情况下它只能判断和猜测,我们就可以学会满足于我们在这种状态下所能达到的目标。

5. Our Capacity suited to our State and Concerns.

5.我们的能力适合于我们的国家和关注的问题。

For though the comprehension of our understandings comes exceeding short of the vast extent of things, yet we shall have cause enough to magnify the bountiful Author of our being, for that proportion and degree of knowledge he has bestowed on us, so far above all the rest of the inhabitants of this our mansion. Men have reason to be well satisfied with what God hath thought fit for them, since he hath given them (as St. Peter says) [words in Greek], whatsoever is necessary for the conveniences of life and information of virtue; and has put within the reach of their discovery, the comfortable provision for this life, and the way that leads to a better. How short soever their knowledge may come of an universal or perfect comprehension of whatsoever is, it yet secures their great concernments, that they have light enough to lead them to the knowledge of their Maker, and the sight of their own duties. Men may find matter sufficient to busy their heads, and employ their hands with variety, delight, and satisfaction, if they will not boldly quarrel with their own constitution, and throw away the blessings their hands are filled with, because they are not big enough to grasp everything. We shall not have much reason to complain of the narrowness of our minds, if we will but employ them about what may be of use to us; for of that they are very capable. And it will be an unpardonable, as well as childish peevishness, if we undervalue the advantages of our knowledge, and neglect to improve it to the ends for which it was given us, because there are some things that are set out of the reach of it. It will be no excuse to an idle and untoward servant, who would not attend his business by candle light, to plead that he had not broad sunshine. The Candle that is set up in us shines bright enough for all our purposes. The discoveries we can make with this ought to satisfy us; and we shall then use our understandings right, when we entertain all objects in that way and proportion that they are suited to our faculties, and upon those grounds they are capable of being proposed to us; and not peremptorily or intemperately require demonstration, and demand certainty, where probability only is to be had, and which is sufficient to govern all our concernments. If we will disbelieve everything, because we cannot certainly know all things, we shall do much what as wisely as he who would not use his legs, but sit still and perish, because he had no wings to fly.

虽然我们的理解力与事物的广度相差甚远,但我们将有足够的理由赞美我们的丰收者,因为他赐予我们的知识比例和程度远远超过我们这所房子里的所有其他居民。人们有理由对上帝认为适合他们的东西感到满意,因为他已经给了他们(如圣彼得所说)[希腊语],凡是生活便利和美德信息所必需的东西;并且把今生的舒适供给和通向更好的道路放在他们发现的范围内。无论他们的知识对任何事物的普遍或完美理解有多短,它都能保证他们的重大关切,即他们有足够的光来引导他们认识他们的造物主,并看到他们自己的职责。如果人们不大胆地与自己的体质争吵,不因为自己的手不够大而丢掉自己的祝福,他们就能找到足够的事情来忙活自己的头脑,用自己的手来做各种事情,并感到满意。如果我们愿意把我们的思想用于对我们有用的事情上,我们就不会有太多理由抱怨我们的思想狭隘;因为他们很有能力这样做。如果我们低估了我们知识的优势,忽视了改善它以达到它被赋予的目的,因为有些东西是它所不能达到的,这将是一种不可原谅的,以及幼稚的抱怨。一个无所事事、不务正业的仆人不愿意在烛光下做事,就不能以他没有广阔的阳光为借口。在我们里面设立的蜡烛对我们所有的目的来说都足够明亮。我们用它所做的发现应该使我们满意;这样我们就会正确地使用我们的理解力,当我们以适合我们能力的方式和比例来对待所有的对象,并在这些基础上向我们提出这些对象;而不是强硬地或无理地要求证明,并要求确定性,而这只是可能性,而且足以支配我们所有的关切。如果我们不相信一切,因为我们不能肯定地知道所有的事情,我们将做得很明智,就像一个人不使用他的腿,而是坐着不动而灭亡,因为他没有翅膀可以飞。

6. Knowledge of our Capacity a Cure of Scepticism and Idleness.

6.6. 对我们能力的了解是对怀疑主义和懒惰的治疗。

When we know our own strength, we shall the better know what to undertake with hopes of success; and when we have well surveyed the POWERS of our own minds, and made some estimate what we may expect from them, we shall not be inclined either to sit still, and not set our thoughts on work at all, in despair of knowing anything; nor on the other side, question everything, and disclaim all knowledge, because some things are not to be understood. It is of great use to the sailor to know the length of his line, though he cannot with it fathom all the depths of the ocean. It is well he knows that it is long enough to reach the bottom, at such places as are necessary to direct his voyage, and caution him against running upon shoals that may ruin him. Our business here is not to know all things, but those which concern our conduct. If we can find out those measures, whereby a rational creature, put in that state in which man is in this world, may and ought to govern his opinions, and actions depending thereon, we need not to be troubled that some other things escape our knowledge.

当我们了解自己的力量时,我们就会更好地知道应该承担什么,并希望获得成功;当我们很好地调查了自己思想的力量,并对我们可能从它们那里得到的东西作出一些估计时,我们就不会倾向于坐以待毙,根本不把心思放在工作上,因为对任何事情都感到绝望;也不会在另一方面质疑一切,并放弃所有知识,因为有些事情是无法理解的。对水手来说,知道他的线的长度是非常有用的,尽管他不能用它来探查海洋的所有深度。他最好知道它有足够长的长度,以便在必要的地方到达海底,指导他的航行,并告诫他不要遇到可能毁掉他的浅滩。我们在这里的任务不是要知道所有的事情,而是要知道那些与我们的行为有关的事情。如果我们能找出那些措施,使一个有理性的生物,在人在这个世界上的那种状态下,可以而且应该支配他的观点和取决于此的行动,我们就不必为其他一些事情逃脱我们的知识而感到烦恼。

7. Occasion of this Essay.

7.本论文的场合。

This was that which gave the first rise to this Essay concerning the understanding. For I thought that the first step towards satisfying several inquiries the mind of man was very apt to run into, was, to take a survey of our own understandings, examine our own powers, and see to what things they were adapted. Till that was done I suspected we began at the wrong end, and in vain sought for satisfaction in a quiet and sure possession of truths that most concerned us, whilst we let loose our thoughts into the vast ocean of Being; as if all that boundless extent were the natural and undoubted possession of our understandings, wherein there was nothing exempt from its decisions, or that escaped its comprehension. Thus men, extending their inquiries beyond their capacities, and letting their thoughts wander into those depths where they can find no sure footing, it is no wonder that they raise questions and multiply disputes, which, never coming to any clear resolution, are proper only to continue and increase their doubts, and to confirm them at last in perfect scepticism. Whereas, were the capacities of our understandings well considered, the extent of our knowledge once discovered, and the horizon found which sets the bounds between the enlightened and dark parts of things; between what is and what is not comprehensible by us, men would perhaps with less scruple acquiesce in the avowed ignorance of the one, and employ their thoughts and discourse with more advantage and satisfaction in the other.

这也是这篇关于理解力的文章的最初起因。因为我认为,要满足人的思想很容易陷入的几个问题,第一步就是对我们自己的理解进行调查,检查我们自己的能力,看看它们适合做什么事情。在这样做之前,我怀疑我们的出发点是错误的,我们徒劳地寻求满足于对与我们最有关的真理的安静和肯定的占有,而我们却把我们的思想放进存在的浩瀚海洋;仿佛所有那无边的范围是我们理解力的自然和毫无疑问的占有,在那里没有什么可以免于它的决定,或逃避它的理解。因此,人们把他们的探究延伸到他们的能力之外,让他们的思想徘徊在那些他们找不到可靠立足点的深处,难怪他们会提出问题和增加争论,而这些问题和争论从未得到任何明确的解决,只是为了继续和增加他们的怀疑,并最终在完美的怀疑论中证实他们。然而,如果充分考虑到我们的理解能力,一旦发现我们的知识范围,并找到确定事物的启蒙部分和黑暗部分之间的界限的地平线;在我们能理解的和不能理解的事物之间,人们也许会不那么顾忌地默认一个人的公开无知,而在另一个人身上更有利地运用他们的思想和讨论。

8. What Idea stands for.

8.理念代表着什么。

Thus much I thought necessary to say concerning the occasion of this inquiry into human Understanding. But, before I proceed on to what I have thought on this subject, I must here in the entrance beg pardon of my reader for the frequent use of the word IDEA, which he will find in the following treatise. It being that term which, I think, serves best to stand for whatsoever is the OBJECT of the understanding when a man thinks, I have used it to express whatever is meant by PHANTASM, NOTION, SPECIES, or WHATEVER IT IS WHICH THE MIND CAN BE EMPLOYED ABOUT IN THINKING; and I could not avoid frequently using it. I presume it will be easily granted me, that there are such IDEAS in men’s minds: every one is conscious of them in himself; and men’s words and actions will satisfy him that they are in others.

我认为有必要就这次对人类理解力的探究说这么多。但是,在我继续谈我对这个问题的看法之前,我必须在这里请读者原谅我经常使用IDEA这个词,他将在以下论文中看到这个词。我认为,这个词最能代表人在思考时的理解对象,我用它来表达幻觉、概念、物种或任何能让人在思考中使用的东西的意思;我不能避免经常使用它。我想大家会很容易同意,人的头脑中存在着这样的观念:每个人都意识到自己有这样的观念;人的言行会让他确信别人有这样的观念。

Our first inquiry then shall be,—how they come into the mind.

那么我们的第一个问题就是:它们是如何进入头脑的。